If you manage rentals, there’s a good chance that you’ve written “no parties” and “quiet hours” into your house rules. Maybe you’ve even incorporated specific decibel levels such as “no noise above 70 dB after 10 p.m.”

But there’s an issue: many people don’t know what those numbers mean in real life. If a guest doesn’t know what 70 dB sounds like, it’s difficult to knowingly keep noise below it. That’s how misunderstandings happen, which can quickly turn a normal evening into guest disputes, neighbor complaints, and even platform warnings or fines.

By the end of this sound level guide, you’ll have a clear mental map of decibel levels, what different noise levels actually sound like, and how to use that knowledge to stop issues before they escalate. We’ll also show how Minut’s privacy‑safe noise monitoring helps you translate numbers into calm, timely action, without recording audio and without compromising guest trust.

Decibels (dB) are the units we use to measure sound. They’re measured on a logarithmic scale, which the Hearing Health Foundations describes as meaning “that loudness is not directly proportional to sound intensity.” This is why a jump from 50 dB to 60 dB isn’t just a little louder, but roughly perceived by the human ear as about twice as loud.

That logarithmic nature is the root of a lot of confusion when cities or platforms set “acceptable noise levels” in dB. A 10 dB increase is a big step up in the room and an even bigger step up through walls and floors.

We also hear differently depending on frequency, duration, and context. That’s why most community rules and building standards use A‑weighted measurements, noted as dBA, which align to how humans perceive sound.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends levels below 30 dBA in bedrooms for quality sleep, and outdoor night noise at building façades around 40–45 dB to avoid sleep disturbance. values that many communities adopt as reference points for policy and planning.

For broader planning, U.S. agencies have long used 55 dB Ldn outside and 45 dB Ldn inside as community benchmarks that balance health and livability, as recommended by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

When platforms and cities translate this into enforcement, they often define noise levels by decibel across day and night windows, or use “X dBA above ambient” tests. That’s where understanding the numbers, and how guests experience sound, becomes essential.

A decibel levels chart helps map numbers to lived experience—decibel examples you can feel. Here are common reference points to anchor your expectations:

There are two more variables that hosts should care about:

.png)

Guests often ask, “what does 50 decibels sound like?” and the answer is it’s a comfortable, everyday level. Picture a normal conversation at the dining table or a TV at low volume while someone else reads nearby. It’s usually acceptable during the day and, in many buildings, during early evening.

At night, context is everything. In quiet buildings with well‑insulated bedrooms, 50 dB inside the guest’s unit may translate to an irritating murmur next door, especially if multiple voices sustain it. When your listing simply says “be respectful,” guests often underestimate this level because it feels “normal” to them. Turning that “normal” into an objective reference of 50 dB helps you coach guests with clarity and fairness.

“So then, what does 70 decibels sound like?” This is the threshold where most short‑term rental noise issues begin. Think group conversations that carry across a room, music playing through portable speakers, or a lively living room with overlapping voices. During the day, it’s common and usually fine. After quiet hours, it’s a different story.

Guests often don’t realize they’ve crossed a line at 70 dB, but that sustained energy can breach building‑interior standards in adjacent apartments, leading to neighborhood noise complaints.

Acceptable noise levels change with time and place. Cities generally allow higher sound levels in decibels in living areas during the day, but make them stricter at night.

While you should always consult local rules, there’s significant overlap across many jurisdictions on interior nighttime caps of 40–45 dBA, with daytime limits 10 dB higher. Examples include Los Angeles County and San Francisco’s interior framework.

For hosts, the goal is to translate these norms into guest‑friendly quiet hours. Most properties start quiet hours between 9 and 11 p.m. and run them through the morning, aligning with community expectations across short‑term rental noise policies and student housing norms.

In the event of a noise complaint, inspectors need to measure noise levels so they can make decisions objectively. But if the guest turns the music off before the inspector arrives, there’s no way to prove that they were too loud. On the other hand, the guests can’t prove that they weren’t being too loud either.

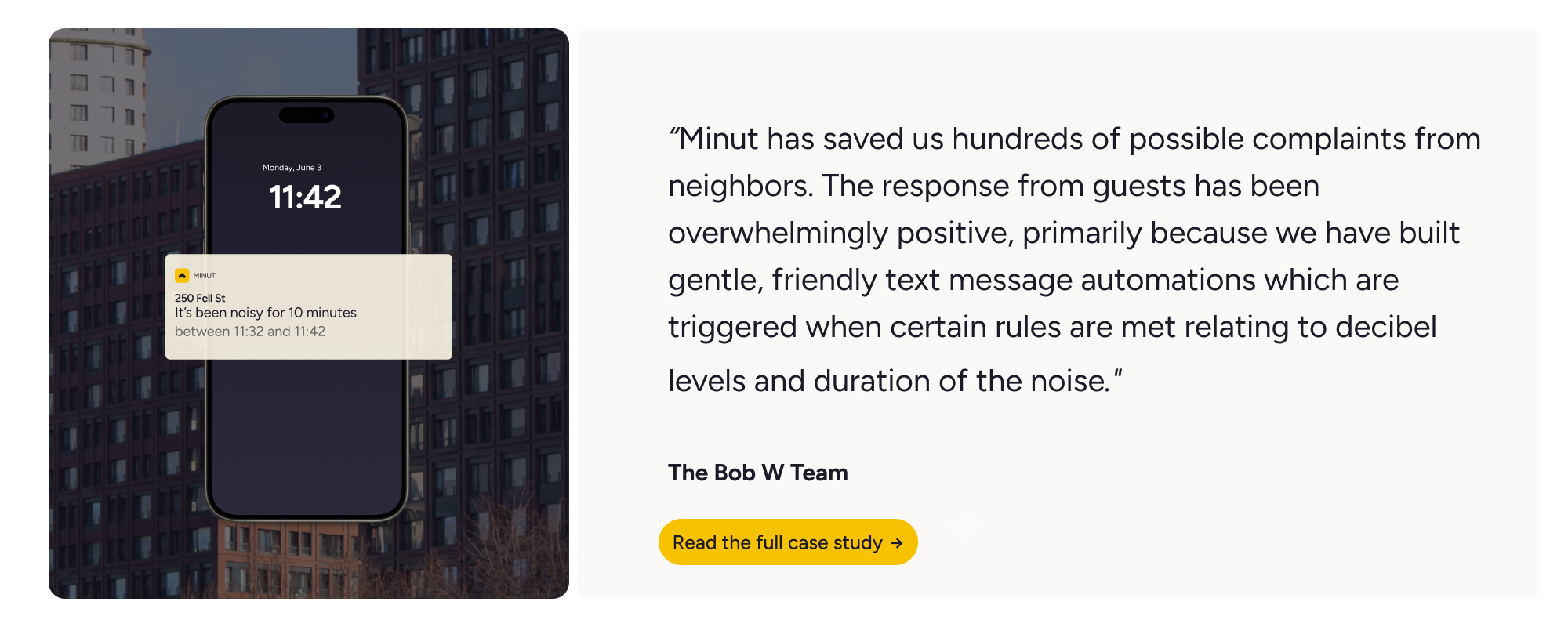

With a noise monitoring device like Minut, the guesswork is removed. It monitors noise levels without recording any audio, and it can send automated messages to the guest if things start to get too loud.

This creates a compliance record hosts can rely on:

Privacy-first noise monitoring devices respect guest privacy by not using cameras or microphones. This can reassure guests, who may otherwise think that they’re being recorded. It’s important to distinguish between audio recording and sound level monitoring:

Platforms recognize the difference. Since April 30, 2024, Airbnb has banned indoor cameras, but allows privacy‑safe “noise decibel monitors” in living areas if disclosed to guests and never placed in bedrooms or bathrooms.

Translating decibel levels into timely, courteous action is where Minut excels. Our platform measures sound levels in decibels without listening or recording, then turns those readings into real‑time insights and alerts so you can intervene long before a neighbor calls.

For hosts, that means fewer issues, fewer platform risk flags, and more predictable operations. For guests, it means clarity and fairness. For neighbors, it means less disruption.

“Be respectful of noise” is well‑intentioned but vague. Guests need specifics they can act on, especially when quiet hours start. Use what you’ve learned about decibel levels to:

Backing up your rules with objective monitoring means you can typically avoid confrontation, because the objective data removes subjectivity and shows the neighbors that you’re a responsible host.

Myth 1: “If guests are indoors, it’s fine.”

Reality: At night, interior caps inside receiving units are often 40–45 dBA. Sustained levels above that next door can be violations, even if your guests are “just inside.”

Myth 2: “Short spikes don’t matter.”

Reality: One cheer won’t trigger enforcement, but a sustained 10–15 minute period often will. That’s why duration‑based alerts are the most effective way to manage quiet vs loud noise levels operationally.

Myth 3: “Only parties cause complaints.”

Reality: Noise can be disruptive below party levels. Loud TVs, music, or people talking across a room can all be louder than the threshold.

With a simple mental map of what different decibel levels sound like and why it matters, you can write clear rules, set the right thresholds, and act early when needed. Decibel levels give you objective, fair ground with guests and neighbors, and they align your practices with city norms and health guidance.

Combining this knowledge with a privacy-safe noise monitor ensures you can be proactive and respectful. A monitor means you can politely inform guests if they’re getting too loud, demonstrates to neighbors that you’re a responsible host, and it gives you objective data to share if it’s needed.

Decibel levels are units to measure sound on a logarithmic scale. Most community and health guidance uses A‑weighted decibels (dBA), which reflect human hearing sensitivity.

It depends on time of day and location. Many U.S. city codes enforce interior nighttime limits around 40–45 dBA inside receiving residences, with higher daytime allowances.

50 dB is a calm, everyday level: normal conversation or a TV at low volume. This level is usually acceptable during the day, but at night in quiet buildings, sustained 50 dB can still be disruptive across walls.

70 dB corresponds to loud talking across a room, a vacuum cleaner, or a busy living room with multiple voices. This is where short‑term rental noise complaints often begin after quiet hours, especially when music with bass is involved.

Complaints commonly start when sustained levels reach the mid‑60s to mid‑70s dB at night. Enforcement generally references interior limits around 40–45 dBA in the receiving unit for nighttime.

Inspectors often take interior readings in the receiving residence or apply “X dBA over ambient” rules. Many cities specify one‑hour averages and quiet‑hours windows.

Yes. Privacy‑safe noise monitoring, such as Minut’s sensor, measures decibel levels and duration without recording content.

Aim to keep nighttime living‑room sound near normal conversation and avoid sustained bass. Operationally, align with interior nighttime caps common in city codes — around 40–45 dBA in receiving units — and lean on WHO’s ≤30 dBA bedroom target for sleep.